As AI adoption accelerates, accountability risks grow. Why leaders need the courage, judgment, and capability to stay responsible when AI gets it wrong.

Every star needs a ladder: what it really takes to shine at work

Performance is not driven by talent alone. It is shaped by the quality of decisions people are able to make under pressure.

Yet most organisations invest heavily in identifying high performers while paying far less attention to the structures that govern judgement, risk-taking, and voice.

When those structures are weak or uneven, even the most capable people hesitate, go quiet, or burn out. The issue is not who gets to shine - but whether the ladder beneath them enables brave decisions rather than reckless ones.

At this time of year, we place a star at the top of the tree. It signals arrival, aspiration, visibility.

In organisations, we talk about “stars” in much the same way: high performers, future leaders, people with potential. But no star reaches the top on its own. It gets there through structure, support, and balance. Not through a single bold leap, but through a series of deliberate steps - often taken quietly, under pressure, and out of sight.

The same is true at work.

Yet most organisations focus far more on identifying stars than on building the ladders that allow people to shine sustainably.

Everyone wants to shine, but not in the same way

Most people want to do well at work. That does not mean everyone wants the same outcome.

Not everyone is chasing promotion, status, or public recognition. For many, success looks like doing work they can be proud of, feeling respected, belonging to a team, providing stability for their family, or contributing meaningfully without burning out.

Most of us do not have a choice about whether we work. But we care deeply about whether our work feels worthwhile and whether we can do it well.

That is where performance really comes from.

Decades of organisational research show that people do their best work when they are supported to make good decisions under pressure - not when they are simply asked to deliver more, or increasingly, more for less. Sustainable performance depends less on individual brilliance and more on the conditions that shape judgement, risk-taking, and behaviour over time.

The unequal ladders behind success

Those conditions are not evenly distributed.

The ladders that allow people to progress - access to sponsorship, advocacy, stretch opportunities, and trust- vary significantly depending on who you are and where you sit in the organisation.

Data from Women in the Workplace illustrates this clearly. At entry level, around 31 percent of women report having a sponsor, compared with 45 percent of men. Women are less likely to be put forward for promotion, less likely to be offered high-visibility opportunities, and more likely to have their performance assessed on past delivery rather than future potential.

Over time, this compounds.

The same research shows that women and men are equally committed to their work. Yet women report higher levels of burnout and, for the first time in the study’s eleven-year history, lower interest in promotion. Crucially, that ambition gap disappears when women receive the same level of support and advocacy as men.

This is not a confidence problem.

It is not a capability problem.

It is a ladder problem.

Burnout is a signal leaders cannot ignore

This pattern does not exist in isolation.

Across the UK workforce, pressure is rising for everyone. Data from the Mental Health Foundation, the CIPD, and the Health and Safety Executive shows that a significant proportion of workers report struggling to cope with stress, experiencing moderate to high levels of work-related pressure, and showing increasing signs of burnout. Women and younger workers report the highest levels of strain.

Burnout is often framed as a personal resilience issue. In reality, it is a systemic signal.

Burnout occurs when people are repeatedly asked to carry emotional, psychological, and relational risk without adequate support or skill to manage it. It reflects decision fatigue and cognitive overload. When this happens, judgement deteriorates. People play safe. They go quiet. Or they push themselves beyond sustainable limits.

None of those outcomes support long-term performance.

What better support actually looks like

When organisations talk about better support, they often focus on visible interventions: wellbeing initiatives, leadership programmes, values statements.

These matter. But on their own, they rarely change how people behave when decisions carry real consequence.

The most consequential support is less visible because it sits beneath behaviour. It is the shared capability to recognise risk, exercise judgement, and act with courage under pressure.

Psychological safety creates the environment. It makes it possible to speak.

What is often missing is the capability to act once that space exists. Reducing fear and creating an inclusive culture does not replace the need for judgement when decisions carry risk. Without courage, psychological safety produces comfort, not progress.

“psychological safety produces comfort, not progress.”

Many organisations underestimate this gap. People may feel able to raise concerns in principle, yet still lack the awareness, language, or confidence to make courageous decisions in practice - particularly when hierarchy, reputation, or relationships are at stake.

Teams do their best work when:

uncertainty can be named without penalty

concerns are raised early rather than buried

disagreement is handled with trust and respect

boundaries are understood as responsibility, not resistance

These are not personality traits. They are learned behaviours, supported by shared language and practice.

Courage lives in everyday decisions

Many leaders say they want courage in their organisations. Far fewer invest in helping people understand how courage actually shows up at work.

Most workplace courage is not dramatic. It appears in small, frequent decisions:

Do I speak now or wait?

Do I challenge this in the room or afterwards?

Do I set a boundary, or absorb the cost myself?

Do I advocate for someone who is not present?

Without self-awareness and shared understanding, these moments are governed by fear, habit, or hierarchy. With training, reflection, and practice, they become intentional.

Decision-making research consistently shows that while professionals report high confidence in their judgement, very few have received formal training in how to make decisions under uncertainty. The result is a confidence–competence gap that increases risk, silence, and burnout.

Courage is not a personality trait.

It is a capability.

Advocacy, boundaries, and shared responsibility

Better ladders also change how advocacy works.

Advocacy is not only about sponsoring high performers. It is about noticing who is being overlooked, who is carrying disproportionate load, and whose voice is not being heard. It requires courage - particularly in environments where speaking up carries reputational or relational risk.

At the same time, people need the skill and permission to advocate for themselves. Setting boundaries, asking for support, or challenging assumptions are acts of courage, especially for those who are not in the majority.

When teams understand these dynamics, advocacy stops being exceptional. It becomes collective.

The leadership opportunity

If organisations want individuals and teams to shine, they need to stop focusing only on the stars and start paying attention to the ladders beneath them.

That means investing in:

environments that support responsible risk-taking

decision awareness under pressure

the courage to speak up and the capacity to listen

the skill to advocate for others, not just oneself

Better support does not remove challenge.

It makes courage possible.

And when people are equipped to take the right risks, at the right time, in the right environment, that is when individuals, teams, and organisations truly shine.

Year-end reflections: A simple tool for brave teams and courageous leaders

Recognising the courage we already carry

Why bravery, clarity and connection matter more than ever

We all carry gifts worth sharing - not just at Christmas, but throughout the year.

For me, that gift is helping people recognise the courage, creativity, ideas, and value they already hold. Their capability to make smart decisions.

Qualities often underestimated, yet essential if individuals, teams, and organisations are to grow, adapt, and thrive in times of change.

Courage and bravery are not exceptional traits reserved for a few. They are human capacities. And when pressure increases - whether through uncertainty, transformation, or complexity - recognising these capacities in ourselves and in one another becomes vital.

Reflecting on courage in leadership and teams

As the year draws to a close, I’ve been reflecting on the leaders, teams, and organisations I’ve supported over the past twelve months.

Across sectors and roles, a consistent pattern emerges: meaningful progress rarely comes from grand gestures or heroic moments. It comes from small, intentional decisions - moments where people choose to act with clarity, integrity, and quiet courage.

Together, we’ve used data-informed insight, research and lived experience to:

develop more sustainable habits

build confidence grounded in evidence

shape behaviours that support trust and performance

move towards ambitions that once felt both daunting and out of reach

These shifts don’t happen overnight. They happen when people feel safe enough to reflect, learn, and act with intention.

The return on investment of brave work

This work delivers measurable results - improved performance, clearer decision-making, stronger collaboration.

But it also returns something far more significant.

Brave teams and courageous leaders report greater purpose, meaning, and well-being. They are not only achieving outcomes - they are more engaged, healthier, and more motivated, because their work aligns with who they are and what they value.

When courage is treated as a practice rather than a personality trait, it becomes a shared capability - one that supports resilience, creativity, and long-term success.

Why simple practices create meaningful change

One of the strongest lessons from this year is that the most impactful practices are often the simplest.

Change rarely begins with sweeping transformation. More often, it starts with a single decision:

to pause rather than rush

to reflect rather than react

to take one small action that creates meaning

These moments of reflection help individuals and teams make sense of what they’ve experienced, turning activity into learning, and effort into insight.

A simple reflection practice for clarity, confidence and courage

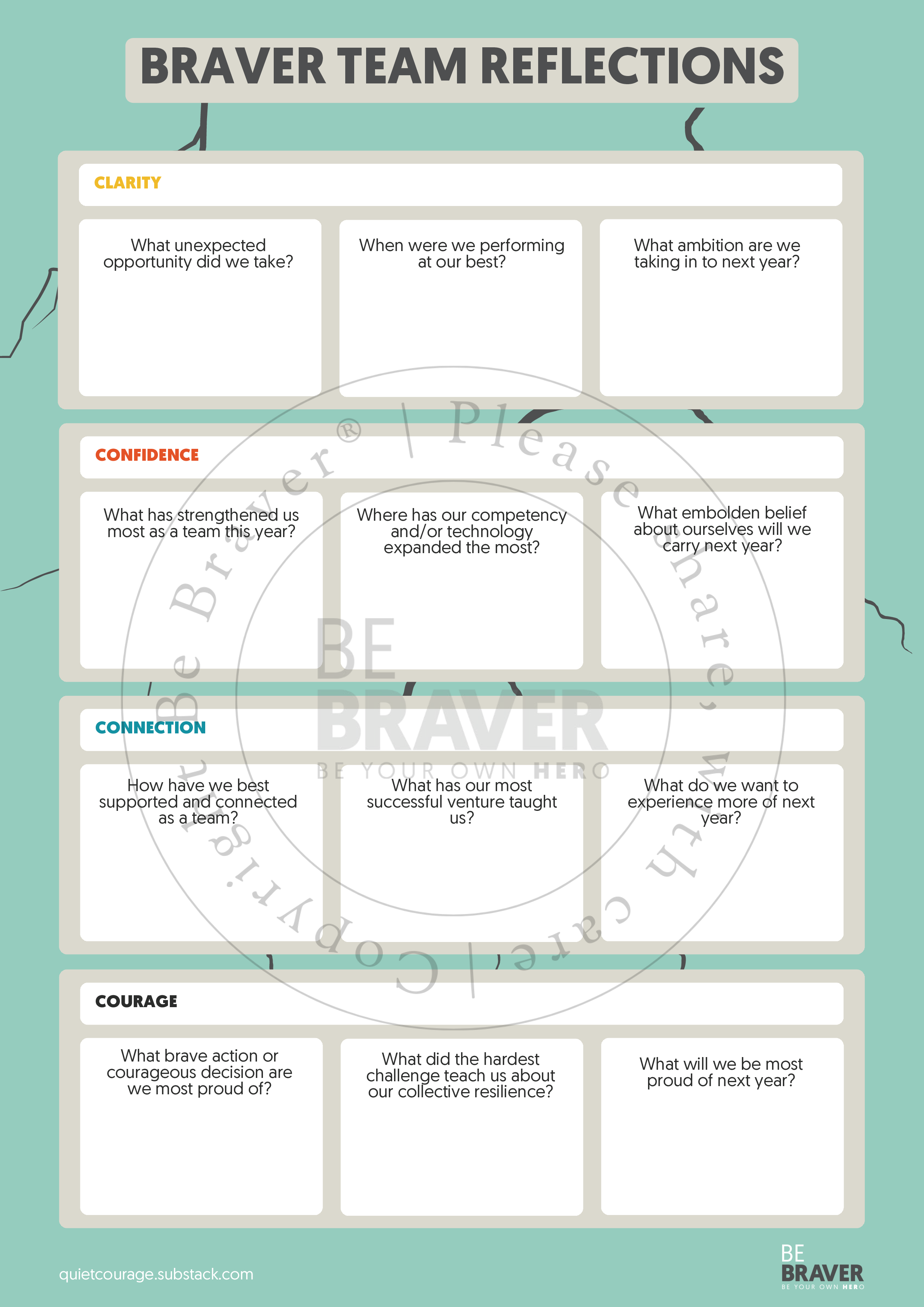

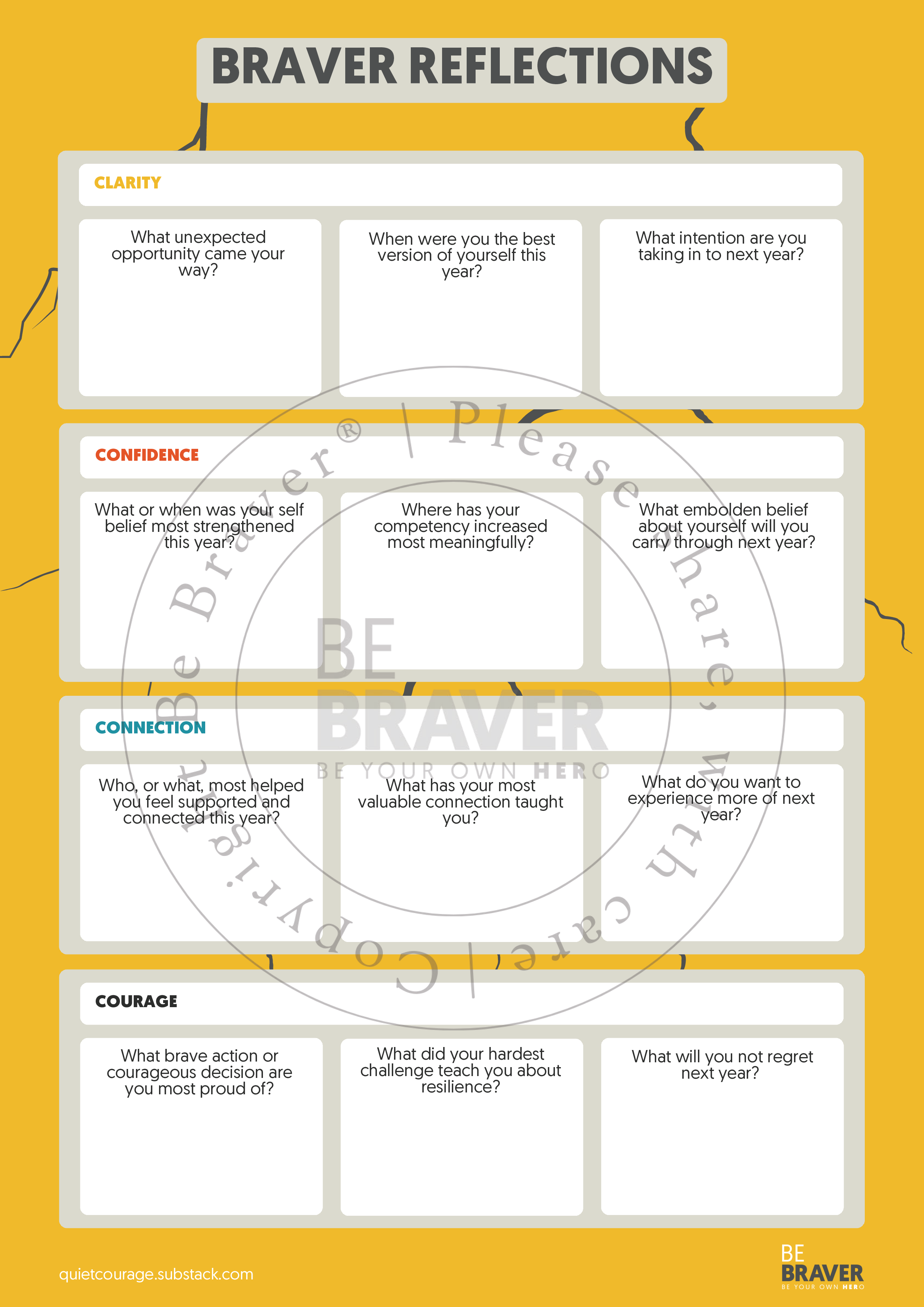

With this in mind, I’m sharing a simple Braver Reflections practice from within the Be Braver® toolkit designed to support both personal growth and team learning.

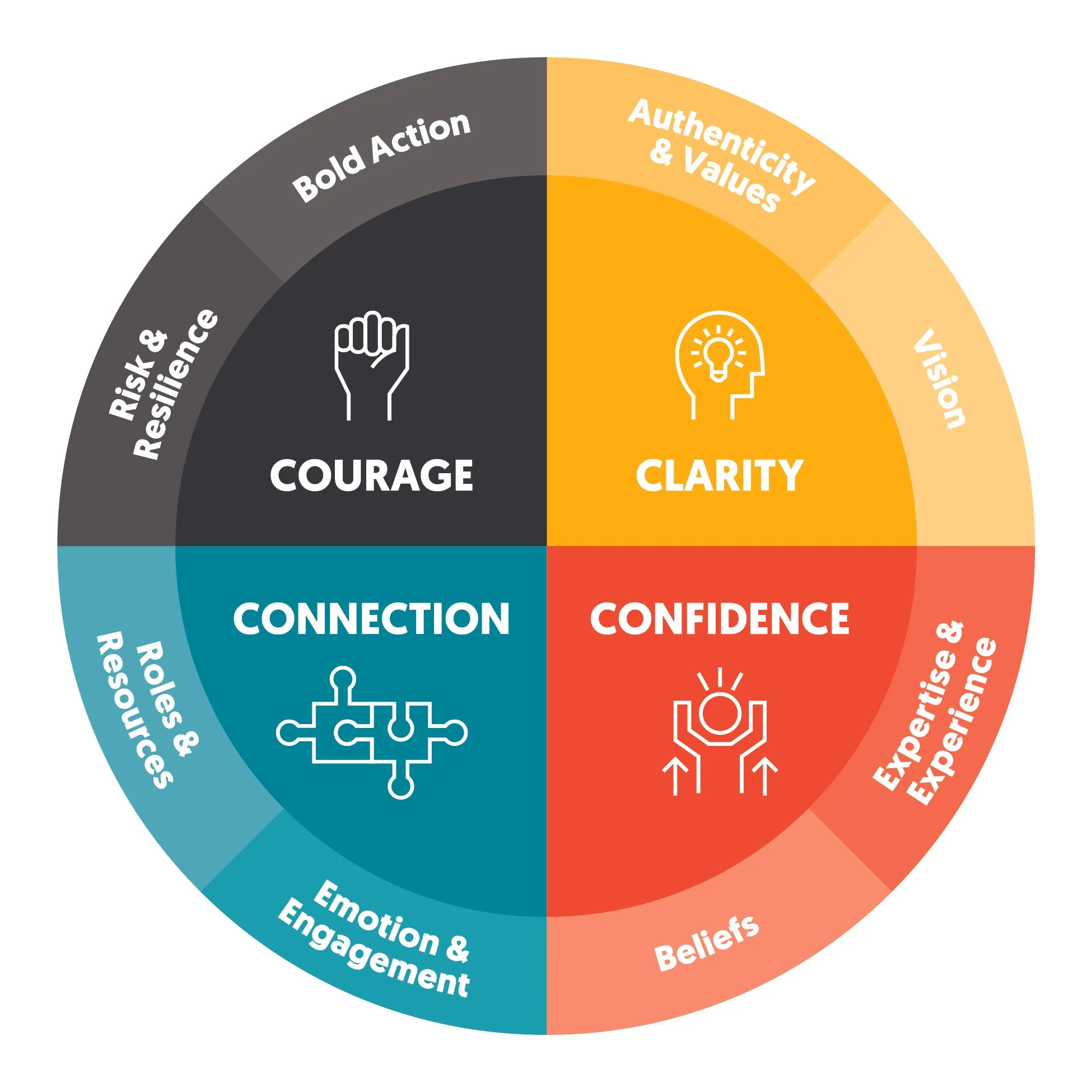

4 Core Foundational Pillars

8 critical practices for living courage and leading braver teams

The questions invite reflection across four essential areas:

Clarity — understanding what mattered and why

Confidence — recognising growth, competence, and belief

Connection — strengthening relationships and shared purpose

Courage — naming the decisions and actions that shaped progress

Used individually or collectively, this practice creates space to pause, learn, and carry forward what truly matters into the year ahead.

Because courage doesn’t always look loud or dramatic.

Often, it begins quietly - with the decision to notice what is already there.

The two faces of courage: leading with both vulnerability and strength

The Missing Humans in Decision Making

The Missing Humans in Decision-Making

In the rush to quantify, regulate, and automate decision-making, we risk missing the invisible human factors that actually shape outcomes. Numbers alone can’t capture the full picture. Culture, human risk, trust, and courage, that which is often unseen can often make the difference.

What happens in our internal worlds, influences how we interpret and respond to that which happens in our external worlds.

Making the Invisible Visible

At the London School of Economics last week, I heard senior regulators and supervisors debate culture in the financial sector. Governors, central bankers, regulators.

The conversation was robust, technical, and deeply important. With the leaders who make decisions that affect us all. The topic ‘Culture in the financial sector’. How refreshing.

And yet, I was struck mostly by what wasn’t said.

There was no mention of neuroscience.

No mention of psychological safety.

No reference to human blind spots.

Bias was discussed - but only in the context of AI, not people.

Distracted by who wasn’t invited to the discussion.

These omissions matter. Ironically. one could say they are visible blind spots.

Because the greatest risks in governance don’t come from algorithms.

I’ve worked a lot delivering leadership programmes for governance professional and coached many. Risks come from humans failing to see, name, or voice the truths that matter most.

When governance aligns with how the brain functions best, boards make sharper decisions, hold healthier debates, and deliver more resilient outcomes.

The Data We Keep Ignoring

The GAABS Workplace Decision-Making report is a sobering read:

46% of leaders lack clarity on the process.

35% equate good outcomes with good decisions.

91% think they are above average in decision-making, while 85% have never had formal training.

Confidence is high. Competence is low. And when leaders conflate outcomes with process, they create false learning loops - reinforcing luck and overlooking blind spots.

Boards fare little better. The Boardroom Decision-Making Effectiveness Index 2025 shows:

Only 44% of directors feel psychologically safe.

Just 24% feel safe to challenge decisions.

Yet boards with high safety are three times more effective in strategy, culture, and governance.

The message is clear: decision-making quality is undermined by overconfidence, poor process clarity, and unsafe cultures. The data confirms what many of us know intuitively: without trust, respect, and courage, boards default to silence, lobbying, and groupthink.

This data legitimises a point in the language of boards. Because many board directors have little experience or literacy in this terrain. Human skills. They often won’t invest in it unless the numbers back it up.

What We’re Missing

We are in danger of missing the humans.

Decision-making isn’t purely rational. It isn’t all numbers, models, and predictable probabilities. Risk management may be the discipline, but it unfolds in environments where humans operate - and humans are messy, unpredictable, and often blind to their own internal judgments.

It cannot all be seen. Neuroscience shows that under perceived threat, the brain’s prefrontal cortex - responsible for reasoning and judgment - shuts down. Psychological safety keeps the brain open, enabling innovation, problem-solving, and foresight.

But safety alone is not enough. Culture creates the space - courage fills it.

Without courageous decision-making, psychological safety risks becoming a talking shop rather than a performance driver. It takes courage for directors to voice dissent, for executives to surface early warning signals, and for regulators to acknowledge when culture, not compliance, is the deeper threat.

The Golden Thread of Courage

Courage is the thread that runs through every effective decision where uncertainty and human risk are present. Psychological safety may open the door, but it is courageous decision-making that walks us through it.

Courage to surface blind spots.

Courage to prioritise ethics over economics.

Courage to create cultures where ambiguity is debated, not silenced.

Courage as a discipline, not a personality trait.

Without courage, psychological safety risks becoming a talking shop. With it, psychological safety lays the foundation. Courageous decision-making builds the structure.

Risk, Uncertainty, and Ambiguity

I don’t claim to have fixed answers here - only reflections as I sit with what I’ve been reading, researching, and listening to. But I do have answers for making the invisible dimensions of human decision making visible. To improve outcomes and culture.

A striking question at the LSE event left me wanting to stand and applaud, came from a psychologist. The question was trying to introduce ethics into the debate, but the response reframed it back into economics - precisely the blind spot I believe we must challenge

That misses something vital.

Risk

Machines are brilliant at calculating probabilities. But humans bring something else: moral weight. A 5% chance of economic contraction is not the same as a 5% chance of mass loss of life. During COVID-19, Jacinda Ardern chose to prioritise lives over GDP. That was not a calculation a machine could make - it was a values-based, courageous decision.Uncertainty

Here, no model gives clarity. What matters is whether leaders can look one another in the eye in the storm and say: we don’t know, but we will act together. Trust and psychological safety are what allow boards and governments to make uncertain calls without paralysis or bravado.Ambiguity

This is where human judgment is most irreplaceable. When the very nature of the threat is unclear, efficiency won’t save us. We need dialogue, diversity of thought, and ethical discernment. Ambiguity requires cultures where dissent is welcomed and moral trade-offs can be openly debated.

And yet, humans are also our own enemy here. We are prone to optimism bias in risk, to freezing in uncertainty, and to silence or hierarchy in ambiguity. The paradox is that we can add what machines lack - trust, courage, ethics - but only if we have leaders courageous enough to create the conditions that surface them rather than bury them.

From Oversight to Foresight

The Boardroom Index notes that high-performing boards engage in scenario planning, surface ethical dilemmas early, and steward culture with accountability. These are not technical achievements. They are human ones.

GAABS shows us that leaders often overestimate their decision-making skill. The Boardroom Index shows us that boards underestimate the importance of psychological safety. And the LSE event showed me how even regulators can overlook the human blind spots driving systemic risk.

Together, they highlight a critical truth: risk management is not just technical. It is cultural and psychological.

The Courageous Decision Agenda

So what must leaders and boards do?

Make the invisible visible

Treat silence, fear, and overconfidence as risk signals, not background noise.

Embed psychological safety

Not as a soft ideal, but as a governance KPI.

Reframe decision quality

Judge by process (values, ethics, bias-awareness), not outcome.

Train courage as a discipline

Through decision workouts, structured feedback, and reflection loops.

Name hidden risks

Status, power dynamics, alienation, chaos - these are not soft issues but material risks to decision quality.

The Human Advantage

Risk isn’t reduced by data alone. It’s reduced when humans make courageous decisions in cultures that allow truth to be spoken.

Psychological safety is the diagnosis. Courageous decision-making is the prescription..

If boards and leaders want to steward their organisations through uncertainty, growth, and disruption, they must go beyond culture change. They must build a new discipline: one where courage, ethics, and human risk awareness are treated as seriously as financial oversight.

That is the Be Braver promise.

Not simply “better culture.”

Not only “braver leaders.”

Not simply a cultural diagnosis. We prescribe courage.

But a pioneering framework for courageous decision-making - to be published soon - fit for the risks of our time.

Brave leadership isn’t about being right - it’s about risking being wrong for the right reasons

Bravery in leadership isn’t performative. It’s principled, high-stakes decision-making in the face of uncertainty - and a willingness to let others see the process.

Would you risk 800,000 customers to stand by your values?

We say we want innovation. We preach resilience. But too often, we punish the leaders who take risks and fail publicly. This piece is about brave leadership - what it really looks like, what it costs, and what it demands of us.

Because brave leadership isn’t about being right. It’s about being prepared to get it wrong for the right reasons.

If we are honest, many of us are afraid of making the wrong call - especially if it costs us customers, revenue, sales. Of being the person held accountable for the decision which saw a decline.

"We will always put our values above our bottom line. End of story."

That’s what Whitney Wolfe Herd said after banning gun imagery on Bumble. Her decision risked user loss and public backlash. She made it anyway.

In most organisations, we measure success by the numbers: retention, upsell, repeat purchase, followers, subscribers, customer tenure.

And yet, not all value is measurable. Not all risk is reckless. And not all leadership is safe.

The ambition is often to find more efficient ways to scale, optimise processes, and deepen customer loyalty.

But what if your best idea means losing customers - at least in the short term? What if you can’t guarantee the test or initiative will succeed?

This is where brave leaders separate themselves. Because implicit in "test and learn" is the reality that things might go wrong. Yet not all cultures make it feel safe to fail.

The best way to ensure we can take smart, collective risks- with the right preparation and the right people - is to work with leaders who model courage. Who create the conditions for it.

And ultimately, to become that kind of leader yourself.

I’ve worked with many of these leaders - often through the Be Braver programme. They’ve done the inner work. They know how to create cultures and behaviours that support courage, not just competence.

I’ve also been searching for examples of this kind of leadership in the public eye. Not just those who lead with conviction behind closed doors, but leaders who display commendable courage - making tough decisions visible when they knew there could be consequences- and visible bravery, showing others what principled action looks like in practice.

Learning Out Loud

One that has stood out is Reed Hastings, co-founder of Netflix. Long before Netflix, during his time leading Pure Software, Hastings reportedly asked his board to replace him - an extraordinary act of self-awareness. The board refused, seeing something in his leadership that even he couldn’t.

Leadership, after all, is a journey - not a destination. We will fall, fail, rise, and fall again.

Hastings has built his leadership philosophy around this reality. In No Rules Rules, co-authored with Erin Meyer, he shares:

"Whisper wins and shout mistakes."

He turns on its head what most of us were taught: celebrate success loudly, hide failures quietly.

But Hastings insists that failures - especially those born of calculated risk - should be shared, studied, and embraced. It’s the hallmark of a learning culture.

He urges leaders to “learn out loud” something I also explore in these Thinking Out Loud pieces. Make your decisions, experiments, and learnings visible. Let others in. Create safety through transparency.

Apply These Insights to Practice:

Start your next team meeting by sharing a recent decision that didn’t deliver the outcome you hoped.

How did you prepare?

Was it reversible?

What did you learn?

Do you regret it?

Ask: “What have we learned this week that we didn’t expect?”

Make retrospectives more about learning than blame.

The Qwikster Debacle

Just imagine being the person whose decision triggered the loss of 800,000 customers and a tanking stock price. That was Reed Hastings.

But instead of deflecting, he took full responsibility citing overconfidence, poor communication, and failure to heed customer signals.

This wasn’t just visible bravery. It was commendable courage.

Apply These Insights to Practice:

Before a bold move, engage those it may impact: colleagues, customers, partners.

Ask: Have we tested this?

Who might this affect in ways we haven’t thought about?

Be willing to publicly course-correct. Your honesty will build more trust than your perfection ever could.

Values Before Revenue

After the Parkland shootings, Whitney Wolfe Herd, founder of Bumble, banned gun images from user profiles.

This was not a branding move. It was a values decision. She received threats. Her team faced real security risks. But she held the line:

“We will always put our values above our bottom line.”

Apply These Insights to Practice:

Define your non-negotiables. Make decisions that align with them even when it costs.

Ask: What does it cost us to compromise? What do we gain by staying true?

Make values visible through action, not just statements.

Whitney Wolfe Herd didn’t just found a company she founded a movement. Bumble was built on a simple shift: women make the first move. It was a rebuke of toxic cultures she’d experienced firsthand.

Purpose wasn’t the marketing. It was the product.

Brave Leadership Is the Long Game

Leadership like this isn’t always celebrated in the moment. It’s often questioned. Sometimes punished. But over time, it lays the foundations for trust, culture, and growth.

So What? Why Does This Matter?

Too many organisations reward only outcomes, not the courage it takes to act without guarantees. But real leadership is principled, transparent action in the face of uncertainty.

Reed Hastings and Whitney Wolfe Herd show us what that looks like.

This is your reminder that brave leadership isn’t loud or perfect. It’s honest. It’s grounded. And it’s needed now more than ever.

So ask yourself:

Where are you being called to be braver?

And what will you do next that others can see - and learn from?